“A group of men and women marching with strike signs,” c. 1909-10. From the Collection of International Ladies Garment Workers Union Photographs (1885-1985) at the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives.

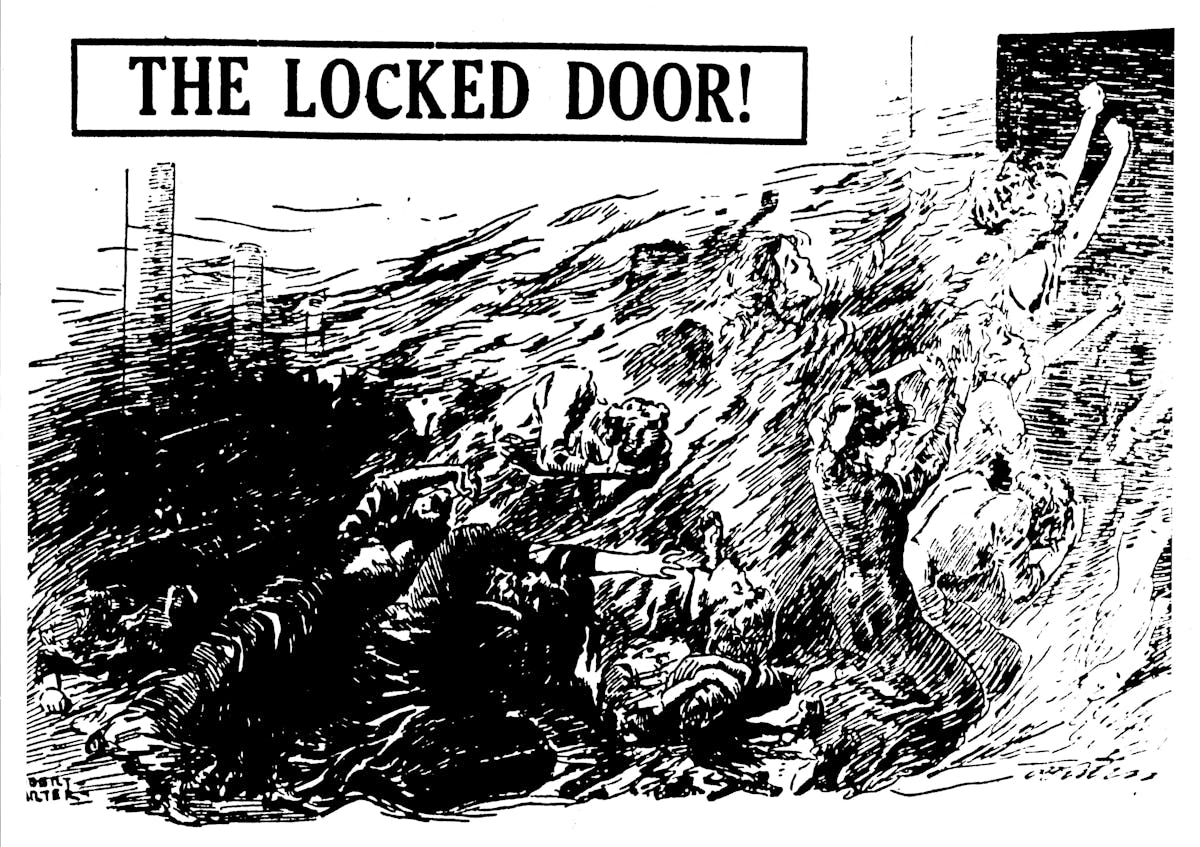

On March 25, 1911 a dropped cigarette caused the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory to go up in flames. Although the blaze was quickly extinguished, it claimed 146 victims, the majority of them young women between the ages of 14 to 23. They were unable to escape the factory because several exit doors were locked from the outside (to prevent unauthorized breaks), there was only one fire escape, and one of the two elevators ceased running. The events of the fire and the resulting trial were heavily covered in newspapers. The New York Times featured not only descriptions of the wreckage, but photographs. Journalists reported on devastated families as they attempted to identify missing relatives, many of whom were beyond recognition. This was not the first deadly labor incident of its time; however, it was the one that caught the public’s attention and ultimately led to major labor reforms. Historically, we think of sewing as a home activity; we picture women embroidering décor or repairing clothing for their families. So, when exactly did it enter factories?

The Age of Outwork

Before the introduction of the sewing machine, the majority of sewing had been considered outwork, and thus done from home. There were some exceptions, but the bulk of sewing was done either at the home or in small workhouses. Outwork, or piecework, was an important source of income for rural families that made it possible for women to earn a supplemental income for their families. It was time-consuming work, between 14 to 16 hours of work per day, with minuscule pay. Pre-cut cloth and supplies were sent to women to produce cheaply made garments or accessories, meaning no mistakes could be made, or income would be lost or significantly diminished. Types of crafts that were commissioned to outworkers included mittens in Maine, handmade lace in Massachusetts and Ayrshire embroidery in Scotland and Ireland.

Sewing machine operators, c. 1910. From the Collection of International Ladies Garment Workers Union Photographs (1885-1985) at the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives.

Enter the Sewing Machine

The first sewing machines appeared in the mid-1700s, however, the sewing machine as recognized today was first introduced by John Fisher in 1844. In 1845, Elias Howe patented his own version of the machine, and Isaac Merritt Singer introduced his in 1851. Early machines were viewed favorably by outworkers, as they could produce goods more quickly, meaning they could save time or, ideally, make more money. Clothing manufacturers began purchasing the machines to produce ready-to-wear clothing, most often cloaks, coats, mantillas, and other outer garments that did not have to be tailored to the body—the precursors to fast fashion. Garment manufacturing exploded in the United States; in 1860 the manufacturing of women’s apparel was listed as an industry in the United States census. By the end of the nineteenth century, the garment industry was the third-largest in the country.

Working Conditions & The Rise of Labor Unions

Significant labor reform did not occur until the twentieth century, although Labor Day was recognized as a holiday as early as 1882, when the first Labor Day was celebrated in New York City (Congress made it a federal holiday in 1894). The conditions in factories began to be exposed in the mid-nineteenth century and unions developed. An 1872 Boston investigation reported there was little or no ventilation in garment sweatshops, many windows and doors were locked, and many workers did not have access to toilets or drinking water. Yet, no significant changes occurred as unions began to strengthen.

The International Ladies' Garment Workers Union

The International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) was founded in 1900. At the time, there were over 18,000 workers employed in the manufacture of blouses alone. The union was originally formed to unite the garment industry and fight for fair labor practices. By 1920, there were around 105,000 members, and it was thus one of the largest unions in the American Federation of Labor (today the AFL-CIO). The ILGWU played a key role in labor rights movements in the first half of the twentieth century and supported all workers in the garment industry.

“The Locked Door!” 1911. From The Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire & the Uprising of 20,000

The 1909 ‘Uprising of 20,000,’ initiated by workers in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory,’ caused the ILGWU’s membership numbers to rise dramatically. The Great Revolt of 1910 saw 60,000 cloakmakers strike, backed by the ILGWU. The concessions to end the strike included a fifty-hour workweek and overtime pay. As importantly, some, though not all, garment factories officially recognized the ILGWU and their demands. These actions were not enough, as the harsh conditions were brought to national attention by the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. Rose Schneiderman, a leader in the Women’s Trade Union League, decried the public’s turning a blind eye to the situation in factories and sweatshops before the fire: “This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Each week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year, thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 143 of us are burned to death.”

The owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, Isaac Harris and Max Blanck, were acquitted at their trial, sparking outrage across the country. Finally, the labor unions began to influence policy as New York City passed legislation to protect the city’s factory workers. They established the Factory Investigating Committee on June 30, 1911, which organized audits to check safety and was the most thorough investigation of factory conditions up to that point. This coincided with the growth of unions and consumers' growing awareness surrounding the conditions in which their clothing was made. This was nearly sixty years after sewing had become mechanized, and over thirty years after the first Labor Day celebration was held.

Labor Reform & the State of the Garment Industry Today

In 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act imposed a minimum wage and required overtime pay for work of more than forty hours per week, inspired by the various labor movements throughout the country. Partially as a result of the law, garment manufacturing moved offshore, to East Europe and Asia, where there were less restrictions and regulations. This has brought many of the same issues faced in America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to different shores. Meanwhile, in America, we’re seeing the resurgence of home sewing. Consumers are becoming more aware of conditions in factories abroad and the devastating effects of the fast fashion industry. Many are supporting ethically-made brands, homemade brands, or brands that are otherwise transparent about their manufacturing sources. We’ve also seen the rise in upcycling, whether through the popularity of thrifting or visible mending. As sewing moved from the home to factories, and back to the home, we have seen how it has not only reflected changing industries but the developing American conscience.

Further Reading

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory

http://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu/index.html

Sweatshops & Factories

The Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives - https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/kheel/

Gary Chaison, “Sweatshops,” in The Berg Companion to Fashion, ed. Valerie Steele.

Sara J. Kadolph and Sara B. Marcketti, “The Textile Industry,” in Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, ed. Phyllis G. Torta.

Yu, “New York Caught Under the Fashion Runway,” in Unravelling the Rag Trade: Immigrant Entrepreneurship in Seven World Cities, ed. Jan Rath.